Services

During the childhood years of peak language acquisition, it is critical to acquaint children with good vocabulary and language usage -- language which, when assimilated, will benefit them in school, college, and throughout their lives. These are the criteria we have used in compiling the following collection of excerpts, downloads, commentary, and book recommendations. Many of these are in the public domain (PD) and downloadable for free, in which cases a link to the online text will be given as well as links to inexpensive and more durable editions. Our children were consulted throughout and their opinions weigh heavily in the choices and critiques. We hope yours find these works similarly absorbing.

There are a few children's books which tower over the rest in their use of imagery and language. Although widely and justly acclaimed for their brilliance, relatively few children have actually read them, and both children and adults have unconsciously accepted as authentic the puerile popularized drivel to which these great works have been reduced in order to make them palatable to the American mass market. The original texts are superb introductions to masterful use of the English language, while the abridgements, retellings, and derivative works tend to be of little more value than the vast popularized undistinguished bulk of commercial television.

The reader will probably note the absence of certain iconic classics such as the Pippi Longstocking books of Astrid Lindgren or The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi. These particular wonderful works were originally written in Swedish and Italian respectively, and even the best translator cannot aspire to produce works that compare with the writings of language artists working in their own native English -- just as reading a translation of Winnie The Pooh (quintessentially English in cultural references as well as language) would probably not be an ideal choice for the student pursuing German lessons . Works by great American writers such as Mark Twain are also absent as the dialects used, though superbly beautiful in their own right, do not represent the formal standard English that best serves the college-bound student studying English online.

It is often very difficult to find full text versions of great classics among the many spurious editions, so we have compiled the following list with links to the books themselves. Fortunately, some of these works are now in the public domain and in these cases links to the online downloadable versions will be given.

One of the truly great (and certainly most celebrated) authors of children's books is A.A. Milne, and while most of his works are still under copyright, one of his early works, Once On A Time, is in the public domain and is available in full text and audio. In common with many other great works on this page, it is perhaps as well appreciated by adults as by children.

Milne was well aware of this phenomenon. From the Preface:

For whom, then, is the book intended? That is the trouble. Unless I can say, "For those, young or old, who like the things which I like," I find it difficult to answer. Is it a children's book? Well, what do we mean by that? Is The Wind in the Willows a children's book? Is Alice in Wonderland? Is Treasure Island? These are masterpieces which we read with pleasure as children, but with how much more pleasure when we are grown-up. In any case what do we mean by "children"? A boy of three, a girl of six, a boy of ten, a girl of fourteen—are they all to like the same thing? And is a book "suitable for a boy of twelve" any more likely to please a boy of twelve than a modern novel is likely to please a man of thirty-seven; even if the novel be described truly as "suitable for a man of thirty-seven"? I confess that I cannot grapple with these difficult problems.

But I am very sure of this: that no one can write a book which children will like, unless he write it for himself first. That being so, I shall say boldly that this is a story for grown-ups. How grown-up I did not realise until I received a letter from an unknown reader a few weeks after its first publication; a letter which said that he was delighted with my clever satires of the Kaiser, Mr. Lloyd George and Mr. Asquith, but he could not be sure which of the characters were meant to be Mr. Winston Churchill and Mr. Bonar Law. Would I tell him on the enclosed postcard? I replied that they were thinly disguised on the title-page as Messrs. Hodder & Stoughton. In fact, it is not that sort of book.

The first of A.A. Milne's more well-known works (as well as one of the best for the early years) is Winnie The Pooh (Available in a boxed set: Winnie-The-Pooh, the House at Pooh Corner, When We Were Very Young, Now We Are Six $29.92).

Unfortunately, the Pooh books are still under copyright and thus not available online, having only briefly lapsed into the public domain and subsequently been put back under extended copyright by business interests. None of the delightful whimsy of the original stories survived their transformation to the screen where American accents and Americanized dialogue (with attendant mangled grammar), and formulaic illustration with great protruding chins transformed them into something

Unfortunately, the Pooh books are still under copyright and thus not available online, having only briefly lapsed into the public domain and subsequently been put back under extended copyright by business interests. None of the delightful whimsy of the original stories survived their transformation to the screen where American accents and Americanized dialogue (with attendant mangled grammar), and formulaic illustration with great protruding chins transformed them into something  quite unrecognizable to lovers of the original "Bear of very little brain."

There are four books: Winnie the Pooh, The House at Pooh Corner, and the two poetry collections: When We Were Very Young and Now We Are Six. Available in a boxed set $29.92 or in a single volume Hardcover: 557 pages $27.20) as well as individually as inexpensive paperbacks. For example: Winnie the Pooh. Various collections and recompilations exist but watch out for the many spurious retellings and derivative works mixed in with genuine editions.

quite unrecognizable to lovers of the original "Bear of very little brain."

There are four books: Winnie the Pooh, The House at Pooh Corner, and the two poetry collections: When We Were Very Young and Now We Are Six. Available in a boxed set $29.92 or in a single volume Hardcover: 557 pages $27.20) as well as individually as inexpensive paperbacks. For example: Winnie the Pooh. Various collections and recompilations exist but watch out for the many spurious retellings and derivative works mixed in with genuine editions.

For those who would like to know more about the original settings, history, and inspiration of the stories, the book The Enchanted Places by Christopher Robin Milne himself

describes how it all came about. Though currently out of print, it can be acquired.

An excerpt from Winnie The Pooh:

It was a fine spring morning in the forest as he started out. Little soft clouds played happily in a blue sky, skipping from time to time in front of the sun as if they had come to put it out, and then sliding away suddenly so that the next might have his turn. Through them and between them the sun shone bravely; and a copse which had worn its firs all the year round seemed old and dowdy now beside the new green lace which the beeches had put on so prettily. Through copse and spinney marched Bear; down open slopes of gorse and heather, over rocky beds of streams, up steep banks of sandstone into the heather again; and so at last, tired and hungry, to the Hundred Acre Wood, for it was in the Hundred Acre Wood that Owl lived.

An excerpt from The House at Pooh Corner:

It was the only place in the Forest where you could sit down carelessly, without getting up again almost at once and looking for somewhere else. Sitting there they could see the whole world spread out until it reached the sky, and whatever there was all the world over was with them in Galleons Lap.Suddenly Christopher Robin began to tell Pooh about some of the things: People called Kings and Queens and something called Factors, and a place called Europe, and an island in the middle of the sea where no ships came, and how you make a Suction Pump (if you want to), and when Knights were Knighted, and what comes from Brazil. And Pooh, his back against one of the sixty-something trees, and his paws folded in front of him, said "Oh!" and "I didn't know," and thought how wonderful it would be to have a Real Brain which could tell you things. And by-and-by Christopher Robin came to an end of the things, and was silent, and he sat there looking out over the world, and wishing it wouldn't stop.

An excerpt from Now We Are Six:

Christopher Robin had wheezles and sneezles

They bundled him into his bed.

They gave him what goes with cold in the nose,

And some more for cold in the head.

They wondered if wheezles could turn into measles,

If sneezles would turn into mumps;

They examined his chest for a rash, and the rest

Of his body for swelling and lumps.

They sent for some doctors in sneezles and wheezles

To tell them what ought to be done.

All sorts and conditions of famous physicians

Came hurrying round at a run.

They all made a note of state of his throat,

They asked if he suffered from thirst;

They asked if the sneezles came after the wheezles,

Or if the first sneezles came first.

They say “If you teasle a sneezle or wheezle,

A measle may easily grow.

But humour or pleazle the wheezle or sneezle,

The measle will certainly go.”

They expounded the reazles for sneezles and wheezles,

The manner of measles when new.

They said, “If he freezles in draughts and in breezles,

The PHTHEEZLES may even ensue.”

Christopher Robin got up in the morning,

The sneezles had vanished away.

And the look of his eye seemed to say to the sky,

"Now, how to amuse them today?"

(This and more poetry by A. A. Milne is to be found here and here.)

Paddington at Large

Paddington at LargeThere are many excerpted and picture-book versions. Be sure to get a full-text exition. Paddington Treasury

The language of Paddington is good and also very accessible to young children. Visit the official Paddington Bear Website.

The next great classic never to be omitted is The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame. In the public domain, the mass market paperback version is a very reasonable $2.99 and a hardcover edition is available for $10.47 (both with uninspired illustrations). Take care not to buy an edition which is abridged or "retold."

Most children have become familiar with Mr. Toad and millions have no doubt experienced "Mr. Toad's Wild Ride" in Disney theme parks. However, the original story of Mole, Rat, Otter,

The next great classic never to be omitted is The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame. In the public domain, the mass market paperback version is a very reasonable $2.99 and a hardcover edition is available for $10.47 (both with uninspired illustrations). Take care not to buy an edition which is abridged or "retold."

Most children have become familiar with Mr. Toad and millions have no doubt experienced "Mr. Toad's Wild Ride" in Disney theme parks. However, the original story of Mole, Rat, Otter,  Badger, and lastly, Toad, is much more than that and, though clearly written for children, the language of the original soars with a mastery of eloquence rarely found in children's literature or elsewhere. The Wind in the Willows is still in print and is in the public domain. It is available online here. The hardcopy versions are all illustrated but some illustrators are particularly good. After much searching, we found that the 75th anniversary Edition containing the brilliantly understated illustrations of E. H. Shepard (who also illustrated Pooh) is available for $13.97 (highly recommended).

Badger, and lastly, Toad, is much more than that and, though clearly written for children, the language of the original soars with a mastery of eloquence rarely found in children's literature or elsewhere. The Wind in the Willows is still in print and is in the public domain. It is available online here. The hardcopy versions are all illustrated but some illustrators are particularly good. After much searching, we found that the 75th anniversary Edition containing the brilliantly understated illustrations of E. H. Shepard (who also illustrated Pooh) is available for $13.97 (highly recommended). Excerpt from The Wind in the Willows:

The rapid nightfall of mid-December had quite beset the little village as they approached it on soft feet over a first thin fall of powdery snow. Little was visible but squares of a dusky orange-red on either side of the street, where the firelight or lamplight of each cottage overflowed through the casements into the dark world without. Most of the low latticed windows were innocent of blinds, and to the lookers-in from outside, the inmates, gathered round the tea-table, absorbed in handiwork, or talking with laughter and gesture, had each that happy grace which is the last thing the skilled actor shall capture -- the natural grace which goes with perfect unconsciousness of observation. Moving at will from one theatre to another, the two spectators, so far from home themselves, had something of wistfulness in their eyes as they watched a cat being stroked, a sleepy child picked up and huddled off to bed, or a tired man stretch and knock out his pipe on the end of a smouldering log.But it was from one little window, with its blind drawn down, a mere blank transparency on the night, that the sense of home and the little curtained world within walls -- the larger stressful world of outside Nature shut out and forgotten -- most pulsated. Close against the white blind hung a bird-cage, clearly silhouetted, every wire, perch, and appurtenance distinct and recognisable, even to yesterday's dull-edged lump of sugar. On the middle perch the fluffy occupant, head tucked well into feathers, seemed so near to them as to be easily stroked, had they tried; even the delicate tips of his plumped-out plumage pencilled plainly on the illuminated screen. As they looked, the sleepy little fellow stirred uneasily, woke, shook himself, and raised his head. They could see the gape of his tiny beak as he yawned in a bored sort of way, looked round, and then settled his head into his back again, while the ruffled feathers gradually subsided into perfect stillness. Then a gust of bitter wind took them in the back of the neck, a small sting of frozen sleet on the skin woke them as from a dream, and they knew their toes to be cold and their legs tired, and their own home distant a weary way.

Two more books by Kenneth Grahame are well worth seeking out though (fortunately or unfortunately) they have never been subjected to demeaning Hollywood treatment and thus never achieved renown. The Golden Age and Dream Days are both PD downloadable but again, the illustrations make the hardcopy worthwhile.

Two more books by Kenneth Grahame are well worth seeking out though (fortunately or unfortunately) they have never been subjected to demeaning Hollywood treatment and thus never achieved renown. The Golden Age and Dream Days are both PD downloadable but again, the illustrations make the hardcopy worthwhile.

Excerpt from The Golden Age:

THE year was in its yellowing time, and the face of Nature a study in old gold, ... the display that Edward and I considered from the rickyard gate. Harold was not in on this scene, being stretched upon the couch of pain; the special disorder stomachic, as usual. The evening before, Edward, in a fit of unwonted amiability, had deigned to carve me out a turnip lantern, an art-and-craft he was peculiarly deft in; and Harold, as the interior of the turnip flew out in scented fragments under the hollowing knife, had eaten largely thereof; regarding all such jetsam as his special perquisite. Now he was dreeing his weird, with such assistance as the chemist could afford. But Edward and I, knowing that this particular field was to be carried to-day, were revelling in the privilege of riding in the empty waggons from the rickyard back to the sheaves, whence we returned toilfully on foot, to career it again over the billowy acres in these great galleys of a stubble sea. It was the nearest approach to sailing that we inland urchins might compass; and hence it ensued, that such stirring scenes as Sir Richard Grenville on the Revenge, the smoke-wreathed Battle of the Nile, and the Death of Nelson, had all been enacted in turn on these dusty quarter decks, as they swayed and bumped afield.

Both The Golden Age and Dream Days were illustrated by E. H. Shepard but an early version also exists with illustrations by the American artist Maxfield Parrish -- very different interpretations but both sets of illustrations are masterpieces in their own right (The Golden Age (Shepard ill.)and Dream Days (Shepard ill.) The Golden Age (Art of Maxfield Parrish Series) and Dream Days (Parrish ill.))

These two works are recollections of childhood in the 19th century English countryside and they demonstrate clearly that Grahame's mastery of language was far greater even than that which is revealed in The Wind in the Willows.

These two works are recollections of childhood in the 19th century English countryside and they demonstrate clearly that Grahame's mastery of language was far greater even than that which is revealed in The Wind in the Willows.

The works of Milne and Grahame, when read in their original form with all their vocabulary and metaphor undumbed by manipulation for the mass market, can test the language capacity of many children and adults. This is part of their beauty.

The Secret Garden

This classic work about an orphaned girl from colonial India who is sent to live with her reclusive uncle in a grand manor house on the Yorkshire moors has been read and reread by millions of children over the years. The language is excellent. Though some Yorkshire dialect is is used, it is clearly distinguishable from the main narrative. This is not a politically correct story. It depicts racial and class distinctions as they existed in the 19th century, yet there are few works that inspire one more completely with the curative powers of nature, love and determination. The Secret Garden is also available online.

The Secret Garden

This classic work about an orphaned girl from colonial India who is sent to live with her reclusive uncle in a grand manor house on the Yorkshire moors has been read and reread by millions of children over the years. The language is excellent. Though some Yorkshire dialect is is used, it is clearly distinguishable from the main narrative. This is not a politically correct story. It depicts racial and class distinctions as they existed in the 19th century, yet there are few works that inspire one more completely with the curative powers of nature, love and determination. The Secret Garden is also available online.

The perpetual adolescence of Peter Pan is a legend almost universally known though few are directly familiar with the delights of the original text, having encountered only derivative popularized versions.

Peter Pan is in the public domain and thus this mass market paperback is a very reasonable $4.99 and the full text (with glossary definitions added in brackets) may be downloaded here for free.

The perpetual adolescence of Peter Pan is a legend almost universally known though few are directly familiar with the delights of the original text, having encountered only derivative popularized versions.

Peter Pan is in the public domain and thus this mass market paperback is a very reasonable $4.99 and the full text (with glossary definitions added in brackets) may be downloaded here for free.Excerpt from the downloadable Peter Pan (with added glossary):

A more villainous-looking lot never hung in a row on Execution dock. Here, a little in advance, ever and again with his head to the ground listening, his great arms bare, pieces of eight in his ears as ornaments, is the handsome Italian Cecco, who cut his name in letters of blood on the back of the governor of the prison at Gao. That gigantic black behind him has had many names since he dropped the one with which dusky mothers still terrify their children on the banks of the Guadjo-mo. Here is Bill Jukes, every inch of him tattooed, the same Bill Jukes who got six dozen on the WALRUS from Flint before he would drop the bag of moidores [Portuguese gold pieces]; and Cookson, said to be Black Murphy's brother (but this was never proved), and Gentleman Starkey, once an usher in a public school and still dainty in his ways of killing; and Skylights (Morgan's Skylights); and the Irish bo'sun Smee, an oddly genial man who stabbed, so to speak, without offence, and was the only Non-conformist in Hook's crew; and Noodler, whose hands were fixed on backwards; and Robt. Mullins and Alf Mason and many another ruffian long known and feared on the Spanish Main.There are of course many well illustrated versions of Pan, our favorite being this hardbound version illustrated by Greg Hildebrant.In the midst of them, the blackest and largest in that dark setting, reclined James Hook, or as he wrote himself, Jas. Hook, of whom it is said he was the only man that the Sea-Cook feared. He lay at his ease in a rough chariot drawn and propelled by his men, and instead of a right hand he had the iron hook with which ever and anon he encouraged them to increase their pace. As dogs this terrible man treated and addressed them, and as dogs they obeyed him. In person he was cadaverous [dead looking] and blackavized [dark faced], and his hair was dressed in long curls, which at a little distance looked like black candles, and gave a singularly threatening expression to his handsome countenance. His eyes were of the blue of the forget-me-not, and of a profound melancholy, save when he was plunging his hook into you, at which time two red spots appeared in them and lit them up horribly. In manner, something of the grand seigneur still clung to him, so that he even ripped you up with an air, and I have been told that he was a RACONTEUR [storyteller] of repute. He was never more sinister than when he was most polite, which is probably the truest test of breeding; and the elegance of his diction, even when he was swearing, no less than the distinction of his demeanour, showed him one of a different cast from his crew. A man of indomitable courage, it was said that the only thing he shied at was the sight of his own blood, which was thick and of an unusual colour. In dress he somewhat aped the attire associated with the name of Charles II, having heard it said in some earlier period of his career that he bore a strange resemblance to the ill-fated Stuarts; and in his mouth he had a holder of his own contrivance which enabled him to smoke two cigars at once. But undoubtedly the grimmest part of him was his iron claw.

The 2003 Universal film Peter Pan (DVD Widescreen Edition or VHS) directed by P.J. Hogan and starring Jason Isaacs, Jeremy Sumpter, and Rachel Hurd-Wood is actually quite faithful to the book, casts a boy in the title role for once, and, as is often the case with film, may well inspire children to read the book. The interpretation is acceptable, the visuals spectacular, and the cast excellent. Even young Sumpter himself looks and acts the part of Pan well (so my daughter attests) until he opens his mouth and spoils the effect entirely by voicing phrases like "have at thee" in an accent much better suited to the malls of American suburbia. This linguistic anomaly grates egregiously against all of the other parts which are so perfectly cast and whose dialogue is so authentically pronounced.

Richard Briers as the pirate "Smee" is an absolute Gem and Carsen Gray as the redskin "Tiger Lily" haranguing Hook in genuine Algonquin is a refreshing treat to any language enthusiast.

The 2003 Universal film Peter Pan (DVD Widescreen Edition or VHS) directed by P.J. Hogan and starring Jason Isaacs, Jeremy Sumpter, and Rachel Hurd-Wood is actually quite faithful to the book, casts a boy in the title role for once, and, as is often the case with film, may well inspire children to read the book. The interpretation is acceptable, the visuals spectacular, and the cast excellent. Even young Sumpter himself looks and acts the part of Pan well (so my daughter attests) until he opens his mouth and spoils the effect entirely by voicing phrases like "have at thee" in an accent much better suited to the malls of American suburbia. This linguistic anomaly grates egregiously against all of the other parts which are so perfectly cast and whose dialogue is so authentically pronounced.

Richard Briers as the pirate "Smee" is an absolute Gem and Carsen Gray as the redskin "Tiger Lily" haranguing Hook in genuine Algonquin is a refreshing treat to any language enthusiast.

The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien is not always considered a children's book, and indeed, much of the subject matter is more suitable for older readers. The Hobbit, The Prelude to The Lord of the Rings and The Lord of the Rings trilogy however, provide the reader with a gradual ascent from child's story to monumental heroic epic through an ever maturing use of language. The Hobbit is in fact a children's book -- or at least it starts that way.

The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien is not always considered a children's book, and indeed, much of the subject matter is more suitable for older readers. The Hobbit, The Prelude to The Lord of the Rings and The Lord of the Rings trilogy however, provide the reader with a gradual ascent from child's story to monumental heroic epic through an ever maturing use of language. The Hobbit is in fact a children's book -- or at least it starts that way.

Excerpt from The Hobbit:

This hobbit was a very well-to-do hobbit, and his name was Baggins. The Bagginses had lived in the neighbourhood of The Hill for time out of mind, and people considered them very respectable, not only because most of them were rich, but also because they never had any adventures or did anything unexpected: you could tell what a Baggins would say on any question without the bother of asking him.As one follows the fellowship through its Middle Earthly travails one finds that the characters are less likely to toss something up in the air as they are to hurl it aloft and less likely to cut an enemy in half than to cleave one in

twain. Professor Tolkien himself was acutely aware of this literary progression and made no effort to amend it.

twain. Professor Tolkien himself was acutely aware of this literary progression and made no effort to amend it.

The Lord of the Rings cannot be compared to any other literary work. The characters, peoples, poetry, history, languages, alphabets, and geography -- all extremely elaborate and complete -- extend far beyond the confines of the story itself. Readers should prepare themselves to become immersed in a world far more complex, consistent, and intriguing than has ever been dreamt into existence by any other author.

Excerpt from The Return of the King:

There was a roar and a great confusion of noise. Fires leaped up and licked the roof. The throbbing grew to a great tumult, and the mountain shook. Sam ran to Frodo and picked him up and carried him out to the door. And there upon the dark threshold of the Sammath Naur, high above the plains of Mordor, such wonder and terror came on him that he stood still forgetting all else, and gazed as one turned to stone.

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings (complete set)

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings (complete set) The Lord of the Rings on Video

The Lord of the Rings on VideoThe Lord Of The Rings - The Motion Picture Trilogy (DVD Full Screen Edition) or on VHS: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King. The tone of The Lord of the Rings spans the gamut from terror and violence to sublimely beautiful and tranquil scenes evoking masterfully a wealth of more subtle emotions. Understandably, given the medium, audience, and time constraints, the epic films of Peter Jackson convey action in vivid and horrific detail while giving short shrift to those other aspects of the work -- when not omitting them altogether. Well worth seeing, The Motion Picture Trilogy including The Fellowship of the Rings, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King (Full Screen Edition) portrays only a small part of Tolkien's unparalleled work and can, by no means, be considered a substitute for reading the books.

The Hobbit (Leatherette Collector's Edition)

The Hobbit (Leatherette Collector's Edition)

The Lord of the Rings (Leatherette Collector's Edition), the full trilogy including The Fellowship of the Rings, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King.

The Lord of the Rings (Leatherette Collector's Edition), the full trilogy including The Fellowship of the Rings, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King.

The Complete Guide to Middle-Earth by Robert Foster is an excellent compendium of Tolkien lore and detail. Every proper noun or significant term in the Hobbit, Lord of the Rings Trilogy, and the Silmarillion is defined and page references given.

The Complete Guide to Middle-Earth by Robert Foster is an excellent compendium of Tolkien lore and detail. Every proper noun or significant term in the Hobbit, Lord of the Rings Trilogy, and the Silmarillion is defined and page references given.

In a very different vein, some relatively obscure works deserve serious attention. One such is Once Round the Sun with its remarkable illustrations by Justin C. Gruelle (the brother of Johnny Gruelle, creator of Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy). You can order Once Round the Sun in hardcover or

In a very different vein, some relatively obscure works deserve serious attention. One such is Once Round the Sun with its remarkable illustrations by Justin C. Gruelle (the brother of Johnny Gruelle, creator of Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy). You can order Once Round the Sun in hardcover or

read it online complete with illustrations.

read it online complete with illustrations.

From the back cover:

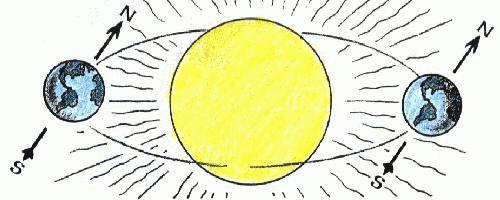

When opening Once Round the Sun, you are about to read the story of Peter and his BIG YEAR. When you have finished you will see that every year, you, like Peter, go on a wonderful journey.Excerpt:Every time your birthday comes round, you know that since your last birthday you have gone all the way around the Sun, and are starting to do it all over again.

I hope you'll like Peter, and make believe you and Peter are just the same -- maybe you are.

Every boy and girl can get the Big Year, if they just know how to ask, and their questions are good questions. Because each of you has an Uncle Peppercorn too, and though he is very small, he is very very important.

"All right!" Uncle Peppercorn jumped on to Peter's shoulder. "You'll do," he said. "just remember that and you can ask anybody anything you want to know."He pointed down again to where the little speck of earth rolled. The third speck from the little sun, to the left of the big fellow.

"Look carefully," Uncle Peppercorn said. "You see where the earth is new. It's going to go all round the sun and you're going with it. Only now you'll KNOW you're going with it. Until it gets back to the same place again, you may ask all the questions you like of everything and everybody on it. And everything will answer you in its own special way. If you ask good questions you'll get good answers. If you ask silly questions you'll get silly answers. The earth and the trees and the grass and the sky, land and sea -- they'll all answer you, until you get back to the same place again."

The Chronicles of Narnia Boxed Set The Chronicles of Narnia, by C.S. Lewis, deserves to be reread at least a few times. Starting in England during the blitz, four children travel through an ancient wardrobe into the land of Narnia, in which time travels at a different pace and a magical realm is waiting for them to save it. Repeated journeys gradually reveal the history and significance of Narnia. The Chronicles of Narnia has been made into an entirely faithful miniseries

available on Video.

available on Video.

The Chronicles of Narnia Boxed Set The Chronicles of Narnia, by C.S. Lewis, deserves to be reread at least a few times. Starting in England during the blitz, four children travel through an ancient wardrobe into the land of Narnia, in which time travels at a different pace and a magical realm is waiting for them to save it. Repeated journeys gradually reveal the history and significance of Narnia. The Chronicles of Narnia has been made into an entirely faithful miniseries

available on Video.

available on Video.

- *** NEW ***

- Online Education

- What is Correct English?

- Acing the SAT

- Homeschool Classes

- Grammar Resources

- SAT Grammar Errors

Site Map

- AES Home

- Featured Resource

- Acing the SAT

- Education Journal

- Grammar Playsheets

- Grammar Resources

- Vocabulary tips

- Vocabulary Quiz

- Software

- Online SAT Resources

- SAT Grammar Errors

- Books on the New SAT

- Vocabulary Books

- Vocabulary List

- Vocabulary Crosswords

- Homeschooling

- Homeschooling

- Homeschooling Classes

- AP exam preparaion

- Homeschooling Books

- Homeschool on the Web

- Homeschooler Central

- Children's books

- The Wind in the Willows

- The Golden Age

- Language Reference

- Common Errors

- Subject/Verb mismatch

- Number (singular/plural)

- Case, declension

- Misplaced Modifiers

- Metaphors

- Mixed Metaphors

- Confused Verbs

- Sentence Fragments

- Run-on Sentences

- Parts of Speech

- Verbs

- Nouns, Pronouns

- Prepositions

- Adjectives

- Online Education

- Studying Online

- Online Higher Education

- Writing Class Online

- Online degrees

- Accredited degrees

- Recommended reading

- Children's books

- Cat Flinging

- Motorscooter Solution

- Wistful Vistas

- Thailand Escape

- Contact us

- Graded Links

Advanced Writing text for the student with little time and a low boredom threshold

Advanced Writing text for the student with little time and a low boredom threshold